Description

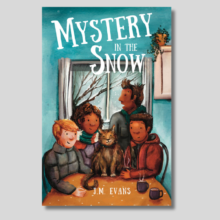

Chapter One

The New Year kicked off to a flying start. Christmas had been great. We’d had a fab party at Beech Bank and the Big Freeze had stayed all through the holidays. We were able to go sledging every day and even try a bit of skiing. It was even good to start a new school term and a new beginning of sessions at Beech Bank, our cool after-school club.

After that, the year seemed to rapidly go downhill somehow. To begin with, there was a thaw. Not a dramatic one, with water pouring off the hillsides and big chunks of ice floating down the river, but a slow, sludgy, depressing kind of affair, with the snow turning grey and soggy, sludge and mud on all the pavements, and the grass and plants looking all squashed and dead when the snow melted. The kind of weather when you can’t even wear decent boots, or they’d be ruined in no time.

But, worse than that, far worse, was what happened to Granddad.

“I just can’t bear to send him back to that place,” said Mum, stashing away the Christmas decorations for another year. “Here, Willow, untangle these lights, could you?”

She handed me a sad-looking tangle of green plastic wire and small glass bulbs, which just recently had twinkled magically, sparkling like stars among a mass of evergreen. Mum is an artist and very creative with Christmas decorations. She really hates seeing the tree and decorations go, so we’re always ages behind everyone else taking them down. Now everything looked drab and depressing, tacky tinsel and browning evergreen that was dropping dead leaves and needles all over the floor.

I couldn’t bear it either. Granddad had stayed over Christmas, and it had been great. He was confused these days, but that didn’t stop him having a good time and a laugh. It was extra work for all of us but we’d got into a kind of routine and didn’t mind.

Except that now my brother and I were back at school and Dad at work, it was Mum who had most of the responsibility. Granddad had been living in an old people’s home for a while now, and was due to go back very soon.

“I can’t bear it,” repeated Mum, piling baubles into a box. “He doesn’t complain much, but I’m sure he doesn’t like it there.”

“If only . . .” I began, and then stopped. Granddad was my dad’s father, not my mum’s, and I knew Dad felt a bit awkward about Mum having to take most of the responsibility for his care. I wasn’t sure it would be fair on Mum either.

Mum looked at me across the box of festive stuff. “You know, I’m sure we could manage if he stayed with us. There’s a day centre in town where he could go mornings, and stay for a hot lunch. We’d just have him afternoons and weekends. He’d be much happier. What do you think?”

I wanted to hug her. “Mum, I think it’s a wonderful idea! We’ll all help!”

So it was arranged. Mind you, there were problems from the start. Bedrooms, for one. We only have three, and over Christmas, my little brother Rowan had given up his room for Granddad. There’d been a bit of a fuss about it, and I felt ashamed thinking about my part in it. My room is quite big, and Mum had wanted to screen off part of it and put a bed in there for Rowan, just temporarily. I wasn’t having it. My room is my refuge, I’ve decorated it myself, all blue and silver, and it’s all just as I want it. The idea of a snotty-nosed little eight-year-old putting his sticky fingers all over my things, even for a short time, made me feel quite ill. So Rowan ended up on the sofa bed in Dad’s study downstairs. He was quite cheerful about it, though Dad had a few worries about his neat and tidy paperwork and office stuff.

“It’s only for sleeping,” Mum told him. “All Rowan’s things can stay in the old room, and he can play in there in the daytime when Granddad’s up and about.”

So that’s how it was. We fell into a routine, Mum dropping off Grandad at the day centre on the way to the shops, and fetching him after lunch. There wasn’t time for her painting any more, and I did sometimes notice her looking wistfully at the stacked canvases in her little work room. But she never complained. And Granddad seemed happy. It was working out.

Until that Tuesday. I came home from Beech Bank Club and found a scene of pandemonium. All the lights were blazing inside and out, a most unusual thing as Mum and Dad are always trying to conserve energy and save the planet. The front door was open and worst of all, an ambulance stood outside, blue lights flashing. My heart seemed to stop and then start hammering hard, and I ran the last few yards, reaching the front gate just as the ambulance men came out with a long shape on a stretcher. Grandad’s pale face and white hair was all I could see, the rest of him was covered with a red blanket. As I stood gaping on the pavement, they slid the stretcher efficiently into the vehicle, and my dad jumped in as well. Then they were gone, lights flashing and siren blaring.

My mum was there beside me suddenly, putting her arm round me, and I saw Rowan in the doorway, outlined against the hall light.

“Willow, I’m sorry, I meant to call you before you got here but it was such a rush getting things together . . .”

My legs were trembling. “What happened?”

“He – he decided he was going for a walk before tea. I told him it wasn’t a good idea, and sat him down with Rowan to play draughts. Your dad was due home. I just went in the kitchen for a few minutes, but he must have decided he was going anyway – I heard the door open and then a kind of thump and a shout – he only got as far as the doorstep, must have slipped.” She was crying now and I could feel her shivering. Rowan was blubbering too. I steered them both inside and shut the door.

Mum pulled herself together. “The ambulance came very quickly, so did your dad. They gave him a shot of morphine – said his hip was probably broken. He was in a lot of pain . . .” Her lips trembled again. It had been a terrible shock. My hands were shaking too, but I filled the kettle and switched it on, wondering briefly why people always make a cup of tea in a crisis. Something to do, I suppose. And plenty of sugar, for shock. I filled up the sugar bowl and tried to speak reassuringly.

“They’ll know what to do in the hospital, Mum. I’m sure they must have fixed lots of broken hips.”

The kettle boiled and I put teabags into mugs. Mum took hers gratefully, and even managed a smile. “Thanks, love. I just hope he won’t hate being in hospital. Or that it won’t make him more confused. I know he’s not my dad, but he’s such an old sweetie . . .”

That made me lose it, too. For a few moments the three of us sniffed and sobbed in between sips of tea, hating the thought of Granddad being in pain, and maybe scared, not knowing what was going on.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.